I’ve always known my ancestry came mainly from northwestern Europe, but I had this quarter that originated from a more unconventional place: Czechoslovakia. Its mystery largely stemmed from its location of forty years behind the Iron Curtain; we simply knew little about it.

In 1988, my great-aunt Betty wrote an account of her parents’ lives. In 1902, Aloise Petruj and Edward Hriza immigrated from Czechoslovakia to the United States. Aloise and Edward were my great-grandparents.

They came mainly for a better life, but Aunt Betty explained another reason. Aloise’s family feared approaching communism. They recognized the coming wave.

Aloise and Edward met on a ship to America where Edward worked as a waiter. Aloise found him kind, cute, and a great dancer. She also liked that he kept clean fingernails and carried a freshly-laundered handkerchief at all times—a sign of a true gentleman, she decided. After their voyage, they reunited with their families in Texas and Colorado and then married.

Eventually, they bought a ranch in remote eastern Oregon where they settled for good. As a young boy, my dad loved visiting his grandparents Aloise and Edward and remembered pumping water on their back porch and crawling between them in bed in the early morning hours.

Edward died at age 59 so relatives don’t remember him as well as Aloise who lived to age 92. Aloise was a beloved figure in the family but I retain only a shadow of a memory of her myself.

I wanted to get to know them both better. Jim and I decided to travel to their homeland in their honor and follow in their footsteps.

Edward and Alosie Hriza with sons Louis and John. Canon City, Colorado

VIENNA, AUSTRIA

The Habsburg Empire ruled central Europe until World War I with little regard to individual countries and boundaries. My great-grandpa Edward grew up in the small village of Lozorno near Bratislava, Slovakia, just an hour east of Vienna. Edward’s father, Blasius, had served as a guard for Emperor Franz Josef, an honored position. But Blasius got into some hot water and abandoned his job, the details of which are sketchy, probably for a reason.

Edward loved Vienna more than any other European city. He traveled extensively and learned the regions’ language as he went. Later he’d use his multi-lingual expertise as a translator.

My great-grandma Aloise grew up in today’s eastern Czech Republic but attended boarding high school in Vienna. Aunt Betty described it as a sort of work-study program where students gained practical farming and ranching skills, ones Aloise found useful in her future life in Pleasant Valley, Oregon.

Alosie Hriza and her sister Sophie Petruj Novesad.

Arrival in Vienna

Now it was Jim’s and my turn to go to Central Europe and see where it all began. While flying from Amsterdam to Vienna, I spotted the Alps. I couldn’t stop “The Hills Are Alive” from ringing in my head.

Jim and I started our time in Vienna at the end of emperors: the Royal Crypt. For centuries, Austria buried its emperors and spouses in these above ground coffins. The bigger the casket, the better. The more ornate, the more important the monarch. The more creepy skulls and crowns, the higher the pecking order. Jim said he felt like he ’d entered Dracula ’s lair.

.jpg)

Jet-lag Is Real

Jim fell asleep mid-sentence at a German pub, twice.

After lunch the next day, we returned to our hotel and both crashed into a two hour nap. We’d gotten little sleep the previous night and were exhausted. After we woke up, we realized we’d missed our Opera House tour.

Music Time

However, nap time made us sufficiently awake for our evening string quartet concert. It would have been embarrassing to fall asleep in our front row seats.

In this intimate space of Vienna’s oldest music hall, our quartet performed Mozart, Hayden and Schubert. I recognized several pieces from my childhood piano lessons, back when I didn’t appreciate learning classical music.

I thought about how my dad, a non-musical guy, ended up taking violin lessons as a kid. Great-grandma Aloise had an uncle who played as a concert violinist in Prague. Uncle John would regularly visit the family and fill their home with song. He promised Aloise his violin—a Stradivarius—when he could no longer play, but she’d long left for America by that time.

My dad took violin lessons as part of a negotiation with his parents. In exchange, he got to transfer to a bigger high school where he could join the football team. Dad’s violin didn’t stick, but now I understand where his mom’s wish for him to play originated. Otherwise these were some pretty lofty goals for a kid born into a logging family in Klamath Falls, Oregon.

As we waited for our quartet to begin, the chatty people behind us offered to take our photo. I told them “Danke" before my jet-lagged brain registered they were British.

Earlier in the day we were in our hotel apartment when the maid arrived. I blurted out “Hola” and she said “Spanish?”

Exhaustion, combined with reflexive shifting to my predominate foreign language, made for a little head-scratching.

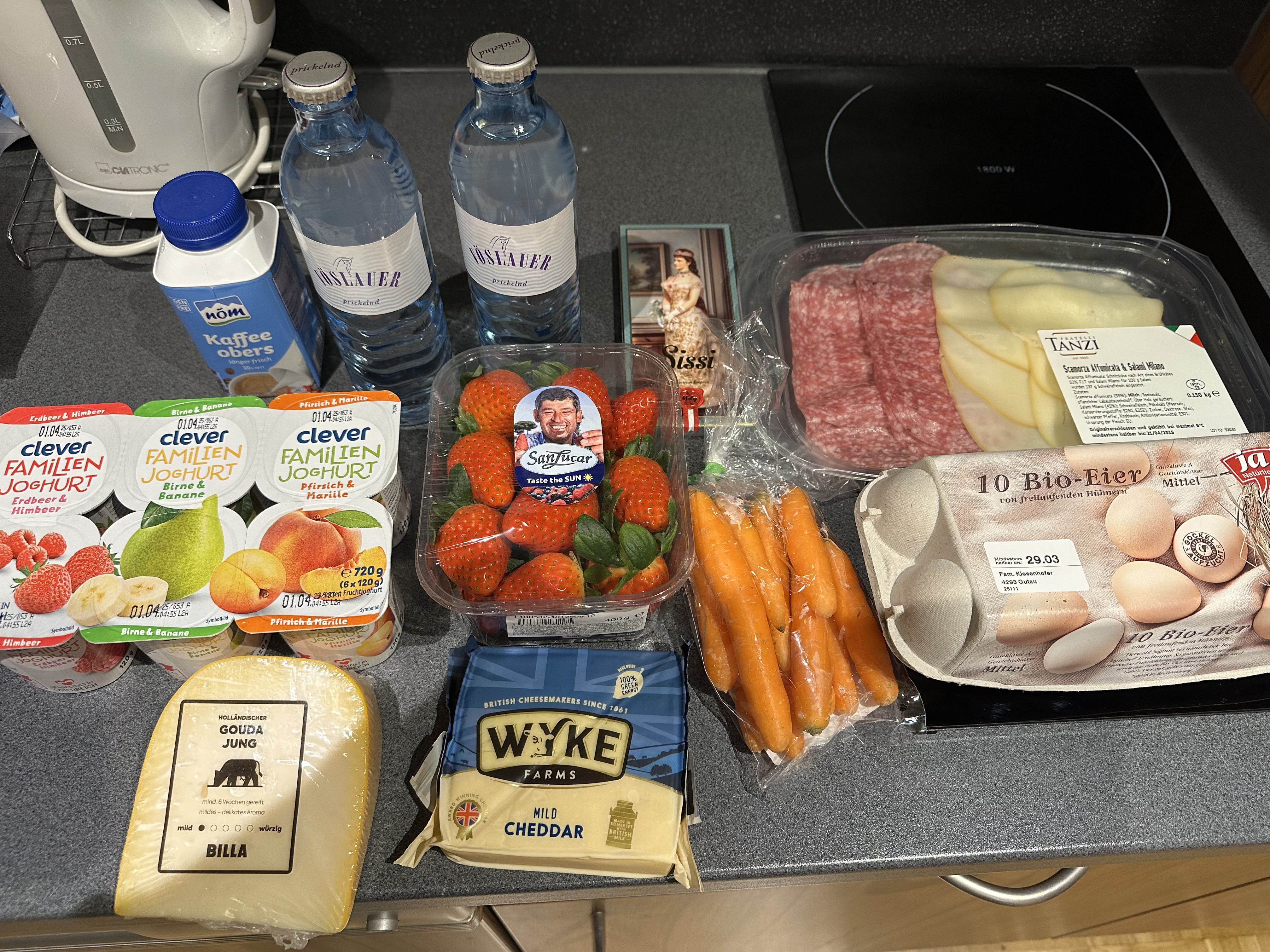

Illiterate Grocery Shopping

We decided to forgo the spendy hotel breakfast and instead buy groceries in the basement of nearby urban mall. We quit with the bananas because we couldn’t figure out how to properly weigh them. We’d set them on the scale and push the only obvious button but nothing seemed to happen. The machine read entirely in German with nobody around to help, so we resorted to pre-packaged produce only. A few days later we encountered a single-purchase option and I finally got my banana.

Habsburg Hotels

Today we passed an architecture school. I imagine it's prestigious studying architecture in a place like Vienna. I could tell it was a school because of the many students out front smoking.

Marble, marble, everywhere. Our aged hotel swims in it, like using wood in Oregon. The marble decor reminds us of Portland ’s Meier & Frank department store in the 1960s, including the scary elevators, though our hotel lift holds only two people, barely.

We have a complicated journey to our apartment and now understand why the receptionist accompanied us the first time. We round corners and pass through two foyers and then get to pick a direction, selecting between left and right marbled duplicates of one another.

One afternoon, loaded with groceries, we chose the wrong route and elevator— something we didn’t yet know existed. We rode to the 4th floor and our apartment had disappeared. We retraced our path down and crossed one of the marble foyers to the flip side, like that Star Trek episode with the alternative universe. Success.

Museums and History Aplenty

Though broke after WWII, Austria invested big bucks into building and rebuilding its museums. They’d lost their power, glory, and empire, but by golly, they still had tons of great stuff to show off.

At the Treasury Museum, the spirited young ticket gal spoke English through a plastic divider. She had a heavy German accent with teeth enmeshed in a collection of rubber bands that rivaled those in my mom’s old desk drawer. I couldn’t take my eyes off her mouth, and not just in my effort to comprehend her.

Ticket gal explained that we could purchase a combo pass for a better deal. We planned to visit more than one art museum so I needed some clarification, but I had difficultly understanding her.

I had flashes of Holocaust films where matrons speak English with clipped German accents, ready to turn on you at any moment. But I had to trust the process and the ticket matron, so I did, and her advice ultimately saved us some time and euros.

Museum Dining

We planned a late lunch at the Natural History Museum when it wasn’t so busy. The museum has a 25,000 year old fertility symbol carved out of stone and a mechanical Allosaurus that could moonlight in a Jurassic Park movie.

The restaurant host asked if we wanted German or English menus. We look sorta German because we are sorta German but don’t speak it. Our cheerful young waiter takes a few minutes to approach us.

Jim: Do you have red wine?

Waiter: It’s not special.

Jim: How about a cappuccino instead?

Waiter: Yes, it’s better.

He takes our order of a large bottle of still water, two tomato-mozzarella- arugula salads, plus an apple strudel for me.

Waiter: Do you want vanilla sauce with the strudel? It’s good with that.

Me: (Establishing that I need vanilla sauce.) Yes to the vanilla sauce, please.

Waiter: Do you want your salads and strudel at the same time, or the strudel later?

Me: How about later?

Waiter: Okay, but you will have to call me over later to order the strudel. (Pointing to his hand-held device) It won’t let me order it separately.

Me: How about all at once then?

Waiter: Okay.

After a few minutes, waiter delivers our bottle of water with two glasses, one of them dirty. I hold up the glass, analyzing the milky smears, drips, and spots.

Waiter: It’s our washing machine. I’ll get you a new glass.

Twenty minutes pass. No new glass. No food.

Waiter: You want to pay now?

Us: We haven’t gotten any food yet.

Waiter: Oh. Okay, sorry. Our kitchen is tired today.

Waiter brings salads and strudel and replacement glass two minutes later. I scarf down my salad in hopes of hitting the strudel while still warm. Yummy. And the vanilla sauce? A smart choice.

German ladies at a nearby table accidentally knock over a drinking glass and it shatters on the ground. They point it out to waiter. He returns several minutes later to sweep most of it up.

Us: We’re ready to pay now.

Waiter: Sorry about the food problem before. The kitchen has a lot of stress today.

Me: What kind of stress?

Waiter: I have been here for two weeks. But I’m a long-time waiter.

Us: Huh? Okay. Danke.

We smile, tip him, and leave.

Hitler Fallout

We toured the Museum of Austrian History in a wing of the former Imperial Palace. Plans originally included a mirror to this grand building, but the Austrian empire died too soon, and now it contains office buildings and museums like this one. We saw photos of Hitler, a native Austrian, on the balcony of the museum, greeting his happy-to-be-occupied people. Thousands turned out to cheer, more than fine with Hitler at the time.

In the past, Austria promoted the narrative that they were more Hitler’s victims than willing participants. But the museum explained how they’ve had to come to terms with their real history with the Nazis.

The Allies also tried to whitewash Austria’s cooperation with Hitler during the war, hoping to encourage resistance among its citizens. Post-war, the West understood that this same narrative helped bring Austrians onboard and safe from communism.

Hofburg palace

Fancy Horses

This morning we watched the presentation of the Lipizzaner stallions, something I probably didn’t appreciate as much as I should have, not being a horse person. All I had to compare was Dolly Parton’s Stampede in Branson, Missouri and the horse carriage competitions at the Oregon State Fair and this was absolutely nothing like that.

But we were glad we went, nonetheless.

German Sausage and Other Exotic Foods

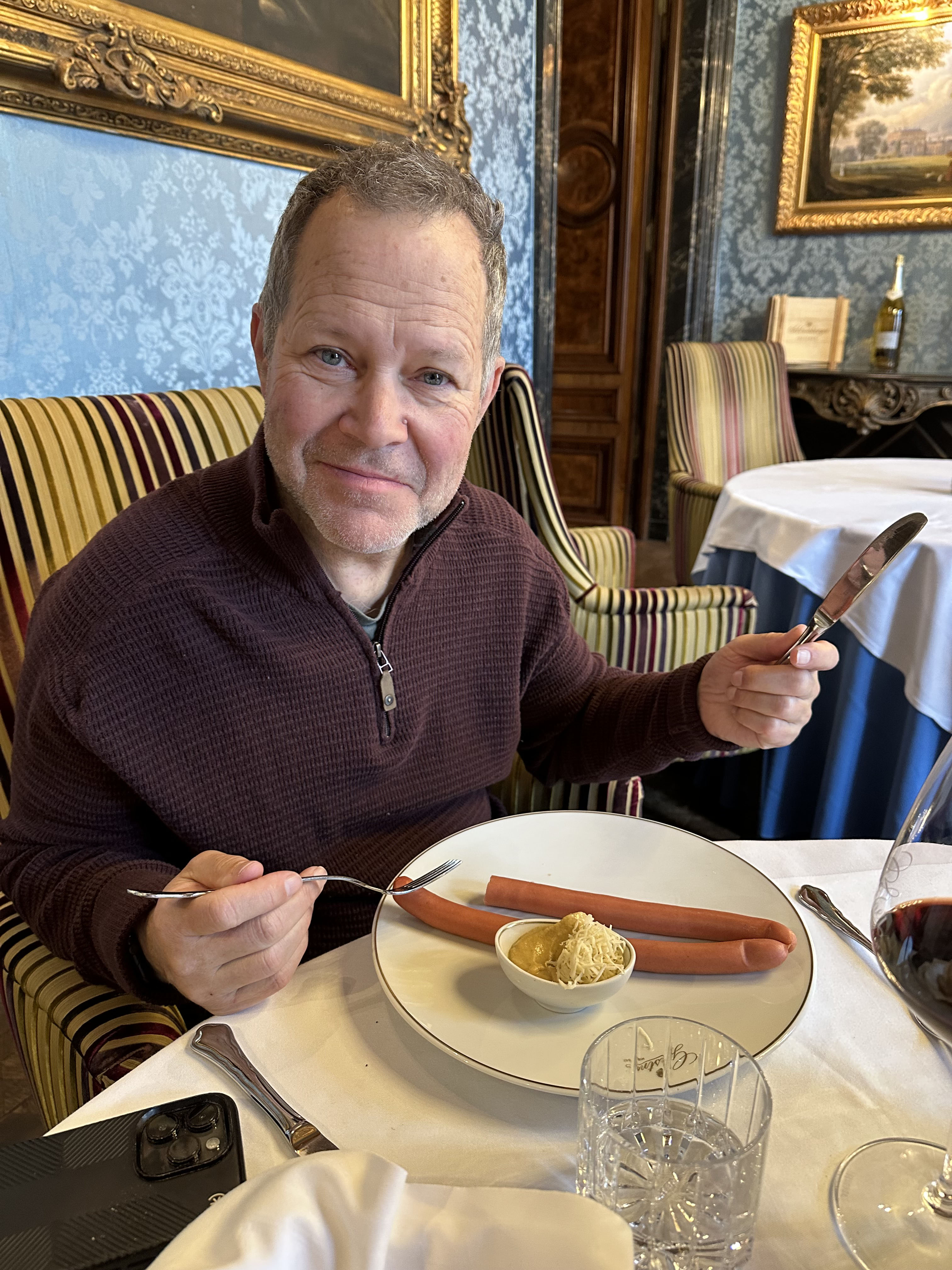

We had lunch at Gerstner Cafe where their napkins say “since 1848.” Funny to think of this fine dining establishment operating during Oregon Trail times. Jim ordered sausage, an anemic tube that resembled an Oscar Mayer hotdog which had stretched and lingered in your elementary school’s fridge too long. But tasty enough with mustard, Jim reported.

We liked the Odysseus Greek restaurant down the road from Schoenbrunn Palace more. The daily specials came only in German and our waiter spoke no English. The middle-aged German businessman next to me offered to translate for us. “May I help?” Yes, please, we said, and then he wanted to discuss politics.

For dinner the next day, we bought street food where Jim finally found the thick sausage of his Vienna dreams, Mount Angel Oktoberfest-style.

Pre-Pubescent Singing Boys

We attended Mass at the Hofburg Chapel with the Vienna Boys Choir this morning. Rick Steves calls them underwhelming but we loved it. I bought tickets for us high on the side where we could watch the boys sing in the back. (Weird to buy tickets for Mass, but that’s how this works.)

The choir had twenty boys plus a handful of grown men accompanied by a small orchestra. The processional included the main priests plus two older assistants, two altar kids and ten fully-developed male choir singers.

The friendly ushers wore suits and a helper priest assisted worshipers up a stair for communion. The main priest, who spoke alternatively in German and English, was welcoming and amiable with a nice sense of humor. He delivered a sermon about Lent, how we need to embrace the darkness in order to make room for the light. It reminded us both of art.

Our own video clip - Vienna Boys Choir

Churches as Tourist Sites

At Saint Stephen’s, Vienna’s 900-hundred-year-old Cathedral, visitors jam the lobby, not wanting to fork-over the fourteen euro entry fee. The ticket matron came from scary Fräulein stock. “Cash only!” she barked. Fortunately we had it. I’m not convinced she didn’t create the cash requirement on the spot; we’d read nothing of it before. We had no issue with paying and it bought us relief from the masses.

We watched the lobby throngs line up with their cell phones trying to take photos of the cathedral through the tall iron gates while we lounged on chairs on the other side. I thought of The Sound of Music again, this time of the nuns peering through their own iron gates as Maria walked up her Austrian wedding aisle, always curious why the nuns didn’t simply cross over to the other side for a better view themselves.

"Sound of Music" wedding scene -Youtube link