Normally I make the 45-minute journey to Corvallis on Thursdays, at least that’s Annie’s best day most weeks. Zach joins us when he’s around and available; he rarely turns down the free meal. A few years ago, a Bible study friend gave me this idea of visiting our college kids and taking them out to eat, and Jim and I have adopted it as our own. Jim typically goes down on Mondays (his day off) or sometimes on the weekend. He offers our kids dinner and pep talks. I offer lunch and shopping—usually for groceries, sometimes for shoes.

Camp Adair Bouquet

When I was a student at Oregon State University nearly 30 years ago, I’d drive from Salem to the campus via Interstate 5; I avoided the back roads. Even though any number of routes delivered me to school in approximately the same time, the freeway just felt faster. Life was more of a hurry for me then. Today I have time for back roads

These days I travel under crumbling railroad trestles and cross the Willamette River where it borders vineyards and summer produce stands. I pull C.D.s from my passenger visor and pop in Annie’s Relient K or Taylor’s mix titled “Old School” that is actually Christian rockers from about five years ago. Old is relative when you’re seventeen.

The roads curves, or rather pivots, at right angles around rectangular farm plots. I visualize early road surveyors petitioning farmers for access across their properties, and the farmers slowly shaking their heads.

Jim at Camp Adair's entrance, Highway 99W

I turn onto Camp Adair Road, the road which connects the angular farm trails to Highway 99W. Camp Adair Road runs as straight as a 100-meter high school sprint. I race through wetlands and wildlife preserves where nature disguises this most curious part of my journey: I’m on the grounds of the abandoned World War II Army training camp called Adair.

The government didn’t bother asking farmers for permission to carve roads through these fields; they simply took the 65,000 acres of low-lands and hills they needed as a harsh reality of the war. While understandably upset at having to sell their pioneer homes, most farmers recognized the greater need for national security and preserving our country’s freedoms and way of life. A few older farmers couldn’t adapt as well and died soon after their uprooting.

Field House buttresses

I cross the railroad tracks that delivered soldiers directly into Camp Adair. Cement pillar buttresses—rows of mammoth number 1’s--outline the Field House. The Field House, big enough for three full-sized basketball courts, functioned as Camp Adair’s recreational center. Soldiers boxed and wrestled here. They played volleyball and basketball. Shirley Temple and Dale Evans dropped by. Joe Louis gave a demonstration of his boxing skills and Jack Benny taped his radio show.

I’m tempted to stop the car and investigate these ruins but worry I’d look foolish to today’s fishermen, dressed as I am in pumps and pink cardigan. In the 1940s, young women probably wore similar clothing to Camp Adair. Groups of single ladies rode buses from Salem for Friday night dances at the Field House under the direction of local “hostesses.” They had first-rate bands because, well, musicians got drafted, too.

Countless couples met and married at Camp Adair, many of them settling in Oregon following the war. But war-time married housing was scarce and in short supply. Oftentimes couples had to rely on creative quarters and the generosity of the local people. Families might take in a young couple for a night and end up adopting them for a year.

On weekend passes soldiers rode open cattle-cars to neighboring towns and cities. Native people throughout the valley rained affection and appreciation upon the soldiers, from individual offers of home-cooked meals and weekend stays, to community contributions of free classes and gym memberships. In Salem they found open doors at places like the YMCA, Willamette University and, of course, the USO.

Camp Adair’s baseball team competed against one of the only other men’s teams around during the war: the Oregon State Penitentiary team. A game played on the prisoner’s home turf in Salem resulted in a 2-2 tie. But at a re-match before a not-so-captive crowd of 2,000 outside prison walls, Camp Adair won 1-0.

Beyond the Field House stands a huge oak tree—the lone survivor of the little town of Wellsdale. A plaque explains that even before the United States entered World War II, the Army scouted out training locations—with an eye on Wellsdale. Then on December 7th 1941, the Japanese dropped their bombs on Pearl Harbor.

A few days later, an Army officer entered Wellsdale’s school and informed the teacher that everyone had to vacate that very afternoon. Within the week, bulldozers erased the town, every little white farm house and red barn. The Army repositioned the railroad line and state highway, and relocated over 600 bodies to a new cemetery. In its place was born Camp Adair, instantly the second-largest population in the state. The property ran six miles wide and ten miles long and contained over 1,800 buildings. An entire city of 40,000, built in just six months.

West of the Field House, on today’s fishing side, more plaques commemorate the camp’s four infantry divisions. Each division trained here for a year before fighting in places such as Belgium, Italy, France, Germany and the Philippines. While their injuries and deaths numbered in the thousands, war records indicate that Camp Adair’s soldiers were exceptionally well-trained.

Camp Adair swamp-lands

Part of the reason for their success lies in Camp Adair’s physical environment. The camp’s terrain and weather is remarkably similar to that which the soldiers faced in Western Europe and the Pacific Islands, and it gave them a distinct training advantage. The Willamette Valley gets lots of rain—just like the battlefields that awaited them. But Adair’s soldiers weren’t so thrilled by the camp’s low-standing water and plentiful rain. While Oregonians normally hibernate indoors during winter months with their books and coffee, the infantry didn’t have that luxury; they had no rain-days at “Swamp Adair.” They marched in the wet, pushed heavy vehicles through the mud, and constantly battled rust on their equipment.

Camp Adair’s terrain replicated the war zone topography of rivers, hills, mountains, and wide open spaces. The Army took the analogy a step further by constructing full-scale Japanese and German villages in the Coffin Butte foothills across Highway 99W. Infantries practiced house-to-house combat in the reproduction German hamlet they named “Insdorf.” German-speaking American G.I.s wore Nazi gear and swastikas to boost the sense of reality.

In these Coffin Butte mountains the Army conducted infantry drills with mortar, grenades, gas chambers, rifles, machine guns, bayonets and howitzer artillery. Because the howitzers had eight mile ranges, the Army ordered evacuation of nearby farm properties. Sometimes civilians driving down Highway 99W were startled by the sight of soldiers attacking dummies with bayonets.

Adair tucked its hospital buildings at the southern tip of the camp, safely away from the action. When the war ended, the Navy inherited the Army hospital and transformed it into a 3,800-bed rehabilitation center. Other parts of the suddenly sparse camp housed hundreds of German and Italian prisoners of war. The military treated the POWs fairly; they had so few problems that most neighbors knew nothing of them. Some of the German prisoners said that the area reminded them of home—the terrain, the forests, the gardens, even the people themselves.

I drive past the old hospital zone (now called Adair Village) and continue four miles down Highway 99W into the northern outskirts of Corvallis, an area called Crescent Valley. Here the Coastal Mountains ring the valley floor in a half-moon shape, the green so brilliant that if Jim painted the scene, he wouldn’t have to exaggerate the color. It feels like home. I’ve always loved this sweet spot of the valley—even before I knew it was my family’s original Eden at the end of the Trail.

Knotts-Owens farmstead

My great-great-great grandfather and grandmother, William and Sylvia Knotts, traveled from Iowa to Oregon in 1845 and to Crescent Valley in 1848 as early pioneers of the Oregon Trail. William was a 40-something widower/dad originally from Maryland; Sylvia was his young bride from Pennsylvania.

Early settlers of the Oregon Territory could claim free land--up to 640 acres (one square mile) for married couples, half that for singles. William and Sylvia chose well and built a cabin; his son later built a farmhouse, which remains standing and in the family. (My distant cousin, an 80-something gentleman I’ve yet to meet, recently sold most of his inherited Knott-family property to the city of Corvallis for preservation. He gets to stay in the 1880 farmhouse as part of a life estate; the farmstead eventually will operate as an historic house facility.)

My G-G-Great-grandparents thrived at farming and having babies. William served as Benton County’s original clerk and held the first legal case on his cabin’s front porch. Sadly, William died ten years after arriving in the Oregon Territory, leaving Sylvia to manage the farm and five young children all by herself. She remarried the following year and had four more children.William and Sylvia’s daughter, Sarah Knotts, was only five years old when her father passed away. Ten years later—at the slight age of 15--Sarah married a local farm boy named James Robinson. Sarah and James moved to Dallas where they raised ten children of their own.

In 1905, Sarah and James’s daughter Josephine, nicknamed “Josie,” married the son of Corvallis’ livery owner. His name was Joseph E. Tyler. (Here my family gets confused because my dad is also Joseph E. Tyler. I’m happy to say that beyond their name, they share little in common.)

Josie Robinson Tyler

Joseph took his delicate bride Josie to a remote section of eastern Oregon to claim land under the Homestead Act. They settled into the hills north of Durkee, Oregon. Durkee is desolate and dry, and its surroundings suffocate with dust and sage brush. Picture the video of Osama Bin Laden tromping around mountains and caves in Afghanistan. It’s like that. The bleak Durkee hills couldn’t have been more removed from Josie’s lush mid-Willamette Valley.

Josie gave birth to three children up on those hills: Jimmy, Doris, and my grandfather, Ray. Josie died a month after delivering Jimmy. She probably had nobody around to help deliver her babies or rescue her from infection or complication afterwards.

Following Josie’s death, Joseph kept my Grandpa Ray and baby Jimmy, but couldn’t--or wouldn’t--raise his only daughter Doris. She was adopted by Baker City’s fire chief and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. Grabner. Joseph and second wife Mighty Mabel reared six more children and several cattle up in their hills.

Ray and Jimmy Tyler

Durkee school-house;

Ray--third step on left;

Jimmy--bottom row on right

Another time Jimmy (my Grandpa Ray’s little brother) somehow angered his father Joseph. Joseph pulled out his belt, but before he could administer the beating, my grandfather stepped between them. Grandpa held a pitchfork in his hands. Joseph backed off.

As soon as he could, my Grandpa Ray escaped his father, a man Grandpa referred to with names we grandchildren weren’t allowed to say. Grandpa Ray abandoned the Durkee hills for other Oregon places with streams and trees and someone around to keep your wife from dying after childbirth. This was good because Grandpa married my Grandma Mary and made my dad; they survived a traumatic birth only because they had a physician who knew what to do. Grandpa also left behind belt whippings and beatings, replacing them with logical consequences. Why Grandpa named my dad after his brutal father, I never thought to ask.

Joseph E. Tyler

a.k.a. “Joe Eddie”

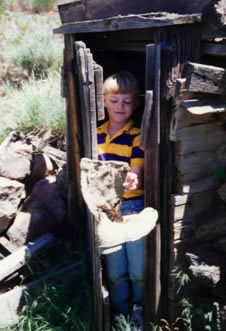

In 1997, my extended family attended a wedding of one of our many cousins still sprinkled throughout eastern Oregon. After the ceremony in Baker City, Cousin Christine Tyler drove us up the dirt road to Joseph and Josie’s Durkee homestead. Christine recently had sold the property but got permission to take us for a look at our family heritage. My dad called the place “God-forsaken.” The rest of us were distracted by thoughts of ticks and rattlesnakes.

Taylor finds a boot in the root cellar

While the homestead house had collapsed, the cellar was mostly intact, so we rooted around for our family roots in the root cellar. Mom and Dad collected artifacts: a horseshoe and a stick of siding. But the best discovery among the dilapidation was a wild rosebush. Had Josie carried these delicate yellow buds with her from the valley? Maybe her own artifacts of home helped her live as long as she did. But how had the roses survived without water? Christine maintains that God waters them from heaven.

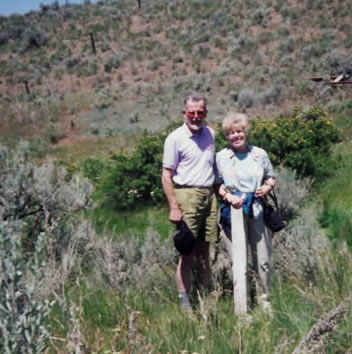

Joe and Ruth Tyler in front of Josie's roses

Dad and Jim both took cuttings from the rosebush and attempted to replant them back in Salem, but neither gardener was successful. Dad knows roses but apparently these roses belong to Josie and nobody else.

Long before my dad was a gardener, he was a good student. Dad studied his way out of eastern Oregon and back to the Willamette Valley. Like Moses, he returned to the land of his ancestors, milk and honey, and the state’s only dental school. There he met my mom Ruth Gregerson, a young nursing student from Idaho. A couple of years later, they married—on the same long weekend my dad graduated from dental school and started his Air Force commission. Dad served three years in Wyoming and then learned how to be an oral surgeon in Philadelphia and Atlanta. That’s where I came in.

Mom says they knew it was time to move home when my older brother and sister started using words like y’all and down yonder. I was one year old during that long road trip from Atlanta to Salem and Mom says I screamed the entire way; I still can’t sleep in cars. My parents suffered a modern version of the Oregon Trail not in a covered wagon, but a station wagon. Mom and Dad delivered us home to our forests and clean water, our mountains and clear air. And the valley’s rich soil grew all five of us children strong.

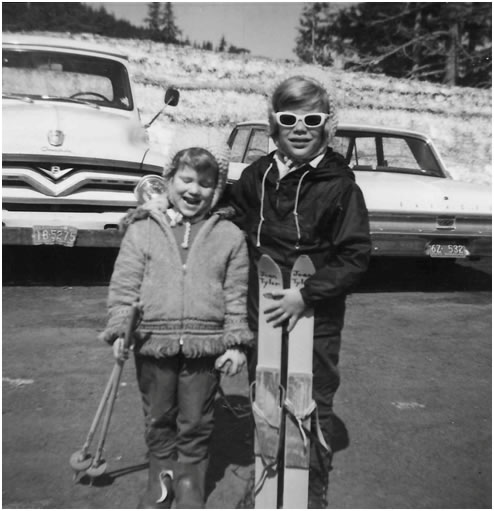

Me (age 3) with big sister Liz, and my very cool personalized wooden skis. Mt. Bachelor, Oregon 1965

(Bachelor was a new resort with one small lodge, outhouses and no running water.)

Jim and I experienced our own years of Air Force residency following dental school. We spent one year in Hampton, Virginia and then two years in Phoenix, Arizona where I withered in the heat. I missed the rain and green terribly. We knew it was our time to return to Oregon when Zach constructed a tree out of Lego blocks; instead of a Douglas-fir, he made a palm tree.

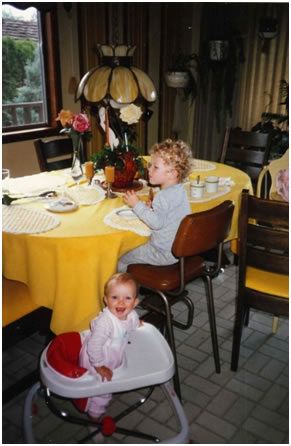

Zach and Annie in Grandma's kitchen

But not everyone is thrilled to come to Oregon, and not just because of the rain. I recall the transplantation of 100,000 soldiers from all 48 states to Camp Adair during World War II. Many of them were young men who had never been away from family and friends before. How frightening it must have been for them to uproot from their homes. How terrifying to face war.

Jean and Jim in Camp Adair ruins

Another Thursday rolls around and I’m on my way to see Annie in Corvallis. Once again I drive through Oregon’s biggest ghost town: Camp Adair. Later I tell Jim I’d like to explore beyond the main road and fishermen’s parking lot. Jim makes a preview hike and suggests we take our dog Bailey there for a walk. I agree.

Not much of the camp itself remains, mostly remains like concrete piers and foundations. After the war ended in 1946, the Army began dismantling all but a handful of buildings, selling off their lumber, doors, toilets, sinks, windows and just about any other item un-nailed and nailed down. The military followed the original plan to restore the site to its pre-War condition, or as much as possible, anyway. But Camp Adair’s chapels--those sacred places where soldiers worshiped and wedded before heading to war? They got special handling. The Army dismantled the camp’s eleven chapels in such a way that they could be put back together someplace else. Believers throughout the state continue praising God in Adair chapels today.

"

Jim and I walk the mowed grass path to the fishermen’s pond, which is kept well-stocked with fish. Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife oversees the Camp Adair property as part of the 2,000 acre E.E. Wilson Wildlife Area. Fishermen sit in the rain and haul in little piles of modest fish, all exactly the same size.

Farther down the wide path we stumble upon a site that resembles parade grounds. Three small structures (which look like concession stands) echo the crescent orientation of the hills. In the center, an empty pole waits for its flag. Our yellow Lab discovers a fire-pit filled with rain water and takes a dive; she emerges charcoal gray. Fortunately, Swamp Adair has plenty of pristine swamp water to erase the fire-pit from her coat.

We cross wooden footbridges and hike paved streets lined with emptiness. We find nothing except the occasional stone footing that suggests a building.

Jim and I return the following week when the weather has improved, this time to explore the north side of Camp Adair Road--the hunting side. A sign lists the creatures for hunting and the dates of the season. (We make note not to visit in September and October.) Dad brought my brother James here in the late 1960s for some father/son pheasant hunting.

The hunting side has fewer ponds than the fishing side but swells of swamps and stone supports. We try decoding the cement footprints into buildings. Post office, Post Exchange, service club, theatre, chapel, barracks?

We slog stretches of road where soldiers once marched in cadence. I don’t know but I’ve been told…Sound off, one, two, THREE, FOUR! The road hasn’t been paved since the war’s end but remains in remarkable condition; it’s been free of motorized traffic for 62 years. Side roads take us to row after row of identical arrangements of piers--four piers across and several times as many down. They must be barracks, we decide. Hundreds of these stone patterns stand in formation across the field.

I negotiate my way through blackberry bushes that camouflage a faded footpath. I inspect a small structure, and outside its doorframe, I spot a spot of color. Daffodils…Creamy daffodils with pale yellow centers.

We return to the ruins of the barracks for a closer look. Blackberry vines crawl from the insides over cement walls, and at the entrance areas, I find clumps of daffodils. Some of the barracks grow all yellow flowers, some all white, others a mixture.

Jim and I gather small bundles. Their bulbs belong to Camp Adair and we’d never uproot them from their soil, but the flowers are renewable. Hunters can shoot rabbit and pheasant here, fishermen can catch trout. I will pick daffodils.

We take the flowers home and they sit in vases next to my computer as I type. They are wartime survivors that return every year, yellow and white, resilient and beautiful.

In the middle of the worries of World War II, someone planted these daffodils, these bulbs of belief in the future. In the middle of my Great-Grandmother Josie’s despair in the Durkee hills, she planted yellow roses and hoped for spring. The flowers are as fresh and full of life as when they first bloomed. We’ll come back next April and remember again.

Note: I learned most of my Camp Adair history from the Benton County Historical Society and John H. Baker’s “Camp Adair: The History of a World War II Cantonment.” Even though I had to look up the word “cantonment,” I thought it was an excellent book.

I got most of my genealogical information from the family tree project Annie did as a teenager. Thanks, Annster! I’ll take you out to lunch on Thursday to express my gratitude, okay?

-